Public concerns about high food prices highlight how meeting basic human needs can’t be taken for granted, even in a country like Australia.

Food prices are but one part of the equation that determines access to food — and generally healthy eating. Just as poverty for some can be hidden within a relatively wealthy community, lack of access to fresh affordable foods can be a problem even in our largest cities.

The term “food desert” describes this concern. It is believed to have been the first coined in the United Kingdom. It’s now widely used in the United States and also in Australia.

People living in food deserts lack easy access to food shops. This is usually due to combinations of:

- travel distances as a result of low-density suburban sprawl,

- limited transport options,

- zoning policies that prohibit the scattering of shops throughout residential areas,

- retailers’ commercial decisions that the household finances of an area won’t support a viable food outlet.

The term “healthy food desert” describes an area where food shops are available, but only a limited number — or none at all — sell fresh and nutritious food.

Our recent research looks at whether food deserts might exist in a major local government area in Western Sydney. We mapped locations of outlets providing food — both healthy and unhealthy food — and of local levels of disadvantage and health problems.

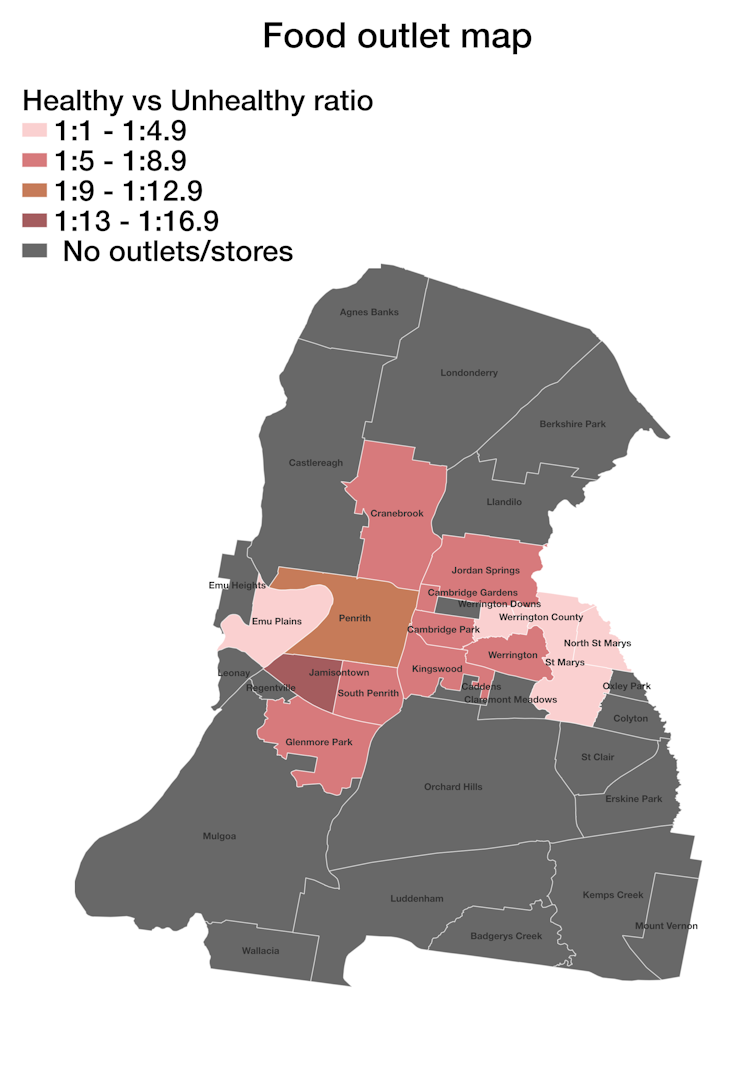

Our initial results are disturbing. We found nearly two-thirds of suburbs have no food stores at all. In those that have them, only 16% of the stores are healthy food outlets.

This map shows the ratio of healthy food outlets to non-healthy outlets for each suburb. Source: A rapid-mapping methodology for local food environments, and associated health actions: the case of Penrith, Australia, Author provided.

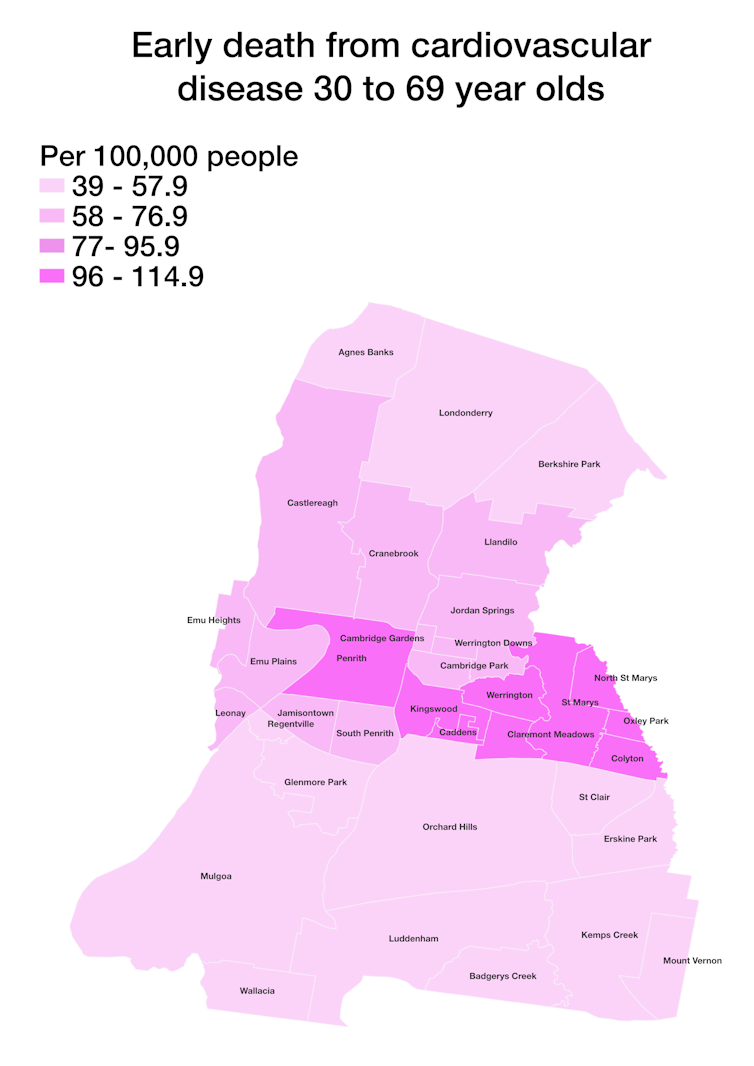

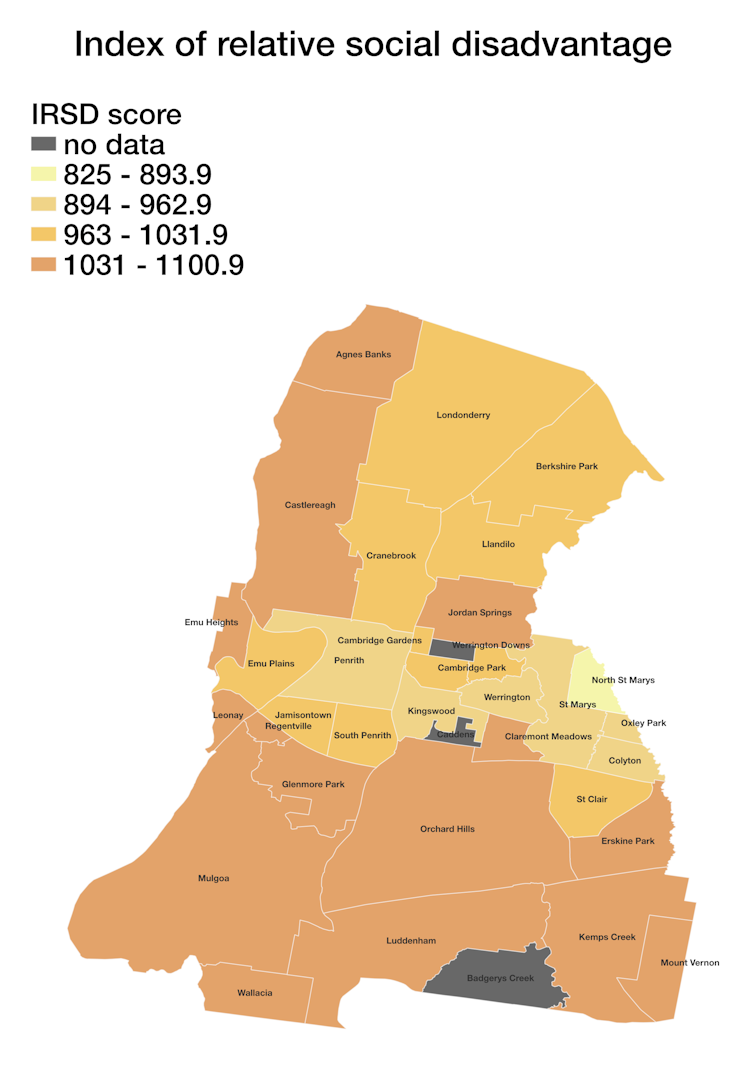

The maps also show strong correlations between these food deserts and areas of poor public health and socioeconomic disadvantage.

How did the study assess the area?

Our research took a rapid appraisal approach to assess whether food deserts might be present in the study area.

Health data from the Australian Health Policy Collaboration indicates concerning rates of overweight and obesity, diabetes and early deaths from cardiovascular disease in these areas.

This map shows rates of early death from cardiovascular disease for each suburb. Source: A rapid-mapping methodology for local food environments, and associated health actions: the case of Penrith, Australia, Author provided.

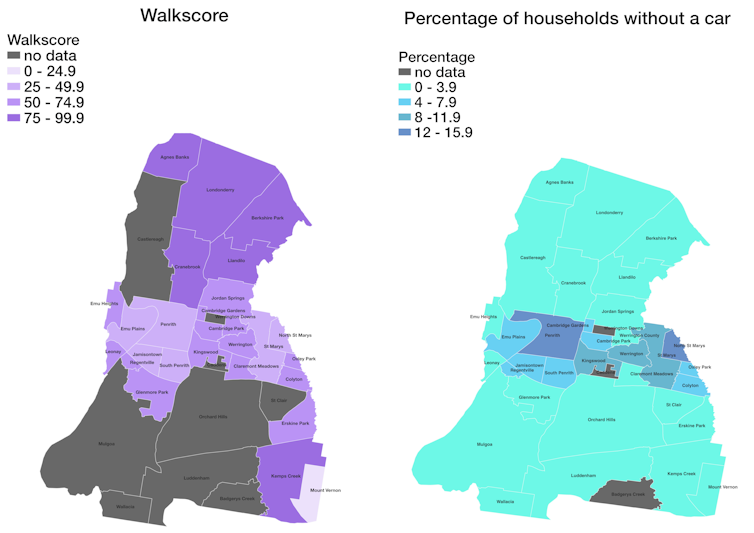

As for the physical environment, the local government area is made up of large single-use residential zones, inconvenient distances to shops and many fast-food outlets. Walk Score ratings of the suburbs indicate how much a car is needed for almost all errands. People who don’t have a car face real hurdles to access affordable, healthier food options.

These maps show the Walk Score and car ownership rates for each suburb (more walkable neighborhoods have a higher Walk Score). Source: A rapid-mapping methodology for local food environments, and associated health actions: the case of Penrith, Australia, Author provided.

We used other data sets (online business directories, store locators and Google maps) to plot the locations of food outlets and make an initial assessment of the types of food they offer. We broadly classified these as “healthy” (chain-operated and independent supermarkets, multicultural grocery stores — mostly Asian and African in this area — and fruit and vegetable shops) and “unhealthy” (independent and franchise takeaway stores and certain restaurants and cafés) .

We mapped the health and livability indicators and food outlets in different colors.

The colored maps offer quick, informative and approachable appraisals of the situation. Because community members can easily interpret them, maps can help prompt community action to improve the situation.

What did the study find?

Overall, “non-healthy” food outlets account for 84% of all food outlets in the local government area.

Further, all food outlets (healthy and non-healthy) are located in 14 suburbs. This means 22 suburbs have no food stores at all. The 14 suburbs with food outlets also commonly have more — at times substantially more — unhealthy than healthy stores.

The mapping also shows a strong correlation between suburbs with a large proportion of unhealthy stores and those with greater levels of disadvantage (using the Australian Bureau of Statistics index of relative socioeconomic disadvantage). The suburb ranked as the most disadvantaged, for instance, has six unhealthy food stores but no healthy food stores. Its Walk Score indicates residents depend on the car and can manage a few errors by foot.

In this map of relative social disadvantage by suburb, lower scores indicate greater disadvantage. Source: A rapid-mapping methodology for local food environments, and associated health actions: the case of Penrith, Australia, Author provided.

Our rapid appraisal method does not provide all the answers. Care needs to be taken so as not to fall into the trap of over-interpretation.

Nor should food outlets themselves be seen as a proxy for healthy or unhealthy eating. They are but one of several factors to be considered in assessing whether people are eating healthily.

What can be done about these issues?

It’s clear that large parts of this urban area do not support residents’ health and well-being by providing good access to healthy food choices.

Urban policy can be effective in eliminating food deserts. Social, land use and community health actions always need to be on the ball and targeted to need.

After all, diet-related choices are not just an outcome of personal preferences. The availability of food outlets, and the range of foods they sell, can influence those choices — and, in turn, nutrition and health.

Our findings pinpoint where targeted investigations should be directed. Determining the exact nature of this lack of choice will help policy makers work out what can be done about it.

It’s an approach well worth taking throughout Australia to check where there might be similar hidden concerns.

Our study lists other proven tools to assist follow-up research that our work has shown is needed. These include:

- onsite appraisals of individual food outlets,

- assessments of the freshness and affordability of items on offer,

- more detailed local accessibility data,

- direct surveys of residents’ experiences of their local food environments.

We all deserve to live and work in places that intrinsically support, rather than withdraw from, healthy choices and behaviors, and therefore our own health.

Ruvimbo Timba, a planning officer at the NSW Department of Planning and Environment and formerly of Western Sydney University, is a co-author of this article.

Nicky Morrison, Professor of Planning and Director of Urban Transformations Research Centre, Western Sydney University and Gregory Paine, Research assistant, Western Sydney University, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.