The end of the Medicaid continuous enrollment provision in March 2023 and the resumption of Medicaid disenrollments after a three-year pause during the pandemic are likely to refocus attention on gaps in Medicaid coverage in the ten states that have not adopted the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) ) Medicaid expansion as of March 2023. During the pandemic, Medicaid enrollment increased and the uninsured rate dropped in large part due to continuous enrollment. Once Medicaid disenrollments resume, the number of people who are uninsured is expected to increase and could rise more steeply in non-expansion states. In expansion states, because all adults with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) are eligible for Medicaid, many current enrollees will remain eligible even if their incomes have risen. However, in non-expansion states, with eligibility thresholds often quite low and largely limited to parents, many of those with incomes below poverty who are no longer eligible for Medicaid will not have access to an affordable coverage option and will likely become uninsured.

Notably, two states have taken recent action to adopt the Medicaid expansion. In November 2022, voters in South Dakota approved the Medicaid expansion through a ballot measure and in March 2023, legislation adopting the Medicaid expansion in North Carolina was signed into law, although the expansion is contingent on passage of a state budget later in the year. If the expansion proceeds as expected in North Carolina, it will become the 41stst expansion state (including the District of Columbia), leaving ten states that have not adopted the expansion. This brief presents estimates of the number and characteristics of uninsured people in the ten non-expansion states who could be reached by Medicaid if their states adopt the Medicaid expansion using data from 2021, the most recent year available. It should be noted that this analysis focuses on the number of uninsured people who would be newly eligible if non-expansion states adopted the expansion; the total number of people who would become eligible for Medicaid is larger because it includes people with incomes 100%-138% FPL who are currently enrolled in Marketplace coverage as well as some who may have other coverage. An overview of the methodology underlying the analysis can be found in the Data and Methods, and more detail is available in the Technical Appendices.

What is the coverage gap?

The coverage gap exists in states that have not adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion for adults who are not eligible for Medicaid coverage or subsidies in the Marketplace. The ACA expanded Medicaid to nonelderly adults with income up to 138% FPL ($14,580 annually for an individual in 2023) with enhanced federal matching funds (now at 90%). This expanded eligibility for low-income parents and newly established Medicaid coverage for adults without dependent children; however, the expansion is effectively optional for states as a result of a 2012 Supreme Court ruling. As of March 2023, 41 states including DC have expanded Medicaid (Figure 1). As noted above, North Carolina has adopted the Medicaid expansion contingent on passage of a state budget later this spring.

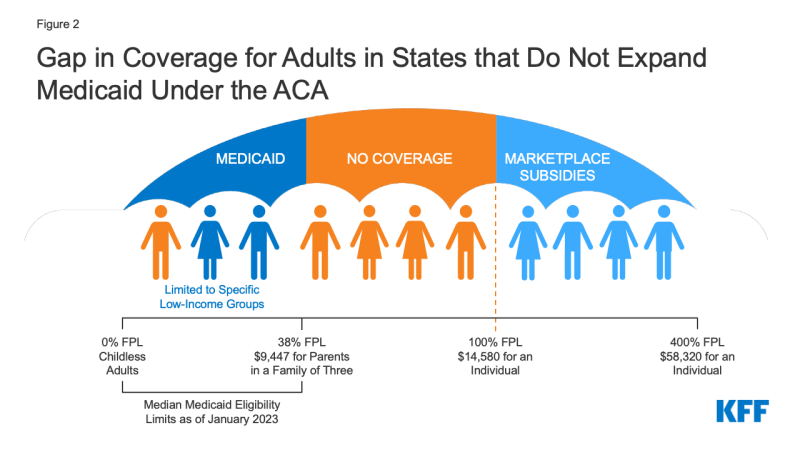

In the remaining ten statesthat have not adopted the Medicaid expansion an estimated 1.9 million individuals fall into the coverage gap. Adults who fall into the coverage gap have incomes above their state’s eligibility for Medicaid but below poverty, making them ineligible for subsidies in the ACA Marketplaces (Figure 2). When enacted, the ACA did not anticipate that states would be permitted to forgo Medicaid expansion; as such, subsidies in the Marketplaces are not available for people with incomes below poverty.

Figure 2: Gap in Coverage for Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid Under the ACA

Medicaid eligibility for adults in states that have not expanded their programs is very low. In these states, the median income limit for parents is just 38% FPL, or an annual income of $9,447 for a family of three in 2023, and in nearly all states not expanding (except Wisconsin through a waiver), childless adults remain ineligible regardless of their income (Figure 3). In Texas, the state with the lowest eligibility threshold, parents in a family of three with incomes above $3,977 annually, or just $331 per month, are not eligible for Medicaid. Because there is no pathway for coverage for childless adults, except in Wisconsin, more than three-quarters (76%) of people in the coverage gap fall into this group.

States that have not implemented the expansion have uninsured rates that are nearly double the rate of expansion states (15.4% compared to 8.1%). People without insurance coverage have worse access to care than people who are insured. One in five uninsured adults in 2021 went without needed medical care due to costs and uninsured people are less likely than those with insurance to receive preventive care and services for major health conditions and chronic diseases.

What are the characteristics of people in the coverage gap?

Adults left in the coverage gap are concentrated in three states in the South. Four in ten people in the coverage gap reside in Texas, which has very limited Medicaid eligibility, and accordingly, a large uninsured population (Figure 4). One in five people in the coverage gap live in Florida, and 13% in Georgia. In total, 97% of those in the coverage gap live in the South. Seven of the 16 states in the South have not adopted the Medicaid expansion, and the region has poorer, uninsured adults and higher uninsured rates compared to other regions.

People in the coverage gap are disproportionately people of color. Nationally, over six in ten (61%) people in the coverage gap are people of color, a share that is higher than for non-elderly adults generally in non-expansion states (47%) and for non-elderly adults nationwide (40 %) (Figure 5). These differences in part explain persisting disparities in health insurance coverage by race/ethnicity.

Despite having low income, nearly six in ten people in the coverage gap are in a family with a worker, and nearly half are working themselves (Figure 6). Adults who work may still have incomes below poverty because they work low-wage jobs. People with incomes below poverty often do not have access to employer-based health insurance or, if available, it is often unaffordable. The most common jobs among adults in the coverage gap are cashier, cook, waiter/waitress, construction worker, maid/house cleaner, retail salesperson, and janitor. For parents in non-expansion states, even part-time work may make them ineligible for Medicaid.

Some people in the coverage gap have significant current health care needs. KFF analysis of the 2021 American Community Survey shows that more than one in six (15%) people in the coverage gap have a functional disability, meaning they have serious difficulties with hearing, vision, cognitive functioning, mobility, self-care, or independent live. Even with functional disabilities, many are not able to qualify for Medicaid through a disability pathway leaving them uninsured. Older adults, age 55-64, an age of increasing health needs, make up 17% of people in the coverage gap. Research has demonstrated that uninsured people in this age range may leave health needs untreated until they become eligible for Medicare at age 65.

How many uninsured could gain coverage if all states adopted the expansion?

If all states adopted the Medicaid expansion, approximately 3.5 million uninsured adults would become newly eligible for Medicaid. This number includes the 1.9 million adults in the coverage gap and an additional 1.6 million uninsured adults with incomes between 100% and 138% FPL, most of whom are currently eligible for Marketplace coverage but not enrolled (Figure 7 and Table 1). Most of the adults who are currently eligible for coverage in the Marketplace qualify for plans with zero premiums; however, even with no premiums, Medicaid could provide more comprehensive benefits and lower cost-sharing compared to Marketplace coverage. The potential number of people who could be reached by Medicaid expansion varies by state.

While not counted in the numbers above, there are an estimated 173,000 people in the coverage gap and 154,000 uninsured adults with incomes 100%-138% FPL who will become eligible for Medicaid if Medicaid expansion proceeds in North Carolina with the passage of a budget ( Table 2). There are an additional 281,000 people in North Carolina who are currently insured in the ACA marketplace with incomes 100%-138% of FPL who will become newly eligible for Medicaid with expansion.

What is the outlook ahead?

Almost ten years after the implementation of the Medicaid expansion in January 2014, a substantial body of research points to a large extent positive effects. KFF reports published in 2020 and 2021 reviewed more than 600 studies and concluded that expansion is linked to gains in coverage, improvements in access and health, and economic benefits for states and providers. More recent studies generally find positive effects related to more specific outcomes such as improved access to care, treatment and outcomes for cancer, chronic conditions, sexual and reproductive health and behavioral health. Studies also point to evidence of reduced racial disparities in coverage and access, reduced mortality and improvements in economic impacts for providers (particularly rural hospitals) and economic stability for individuals.

While attempts to pass federal legislation to address the coverage gap nationally failed, states that had just implemented Medicaid expansion would receive a temporary fiscal incentives under the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). Under ARPA, states that newly adopted expansion are eligible for an additional 5 percentage point increase in the state’s traditional match rate (FMAP) for two years. This incentive does not apply to the expanding population; states are required to cover 10% of the cost of Medicaid expansion, with the federal government covering 90%. The traditional FMAP applies to most spending for all non-expansion groups (children, parents and eligible people based on age 65 plus or disability) ; Medicaid spending for non-expansion groups is much larger than spending for the expansion group. KFF analysis shows that all non-expansion states could see a net fiscal benefit over a two-year period if they adopted the expansion. For the two states that recently adopted the expansion, South Dakota and North Carolina, the estimated fiscal benefit is $60 million and $1.2 billion, respectively.

Seven of the last eight states to adopt expansion did so through a ballot measure; however, that is not an option in most other non-expansion states. Every state, except North Carolina, that has adopted expansion since 2019 has been done so not through legislative or executive processes, but as a result of a successful ballot initiative. Most recently, in South Dakota voters approved a ballot question in November 2022. Although expansion ballot initiatives have been successful in all seven states where they have gone to voters (Idaho, Maine, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Utah), most of the remaining non-expansion states do not have ballot initiative processes. North Carolina is the first state to adopt expansion through a legislative process since Virginia was adopted in 2019.

Expansion could help stem increase in the number of people who are uninsured as the Medicaid continuous enrollment provision ends and states resume disenrollments after a three year pause during the pandemic. All states have experienced significant Medicaid enrollment growth as a result of legislation enacted early in the pandemic that states prohibited disenrolling people from Medicaid in exchange for enhanced federal matching funds. The increase in Medicaid coverage has been a key factor contributing to the decline in the uninsured rate. When the continuous enrollment provision expires on March 31, 2023 and states resume regular Medicaid disenrollments, millions are expected to lose Medicaid if they are no longer eligible or if they face barriers completing their renewals. While most people who are determined to no longer be eligible in expansion states will qualify for other coverage, either through the Marketplace or through an employer, in non-expansion states, poor parents who are no longer eligible for Medicaid will likely fall into the coverage gap and become uninsured.